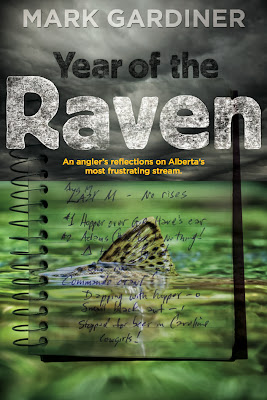

Year of the Raven

Wednesday, October 18, 2017

Click the cover to buy now! Over 200 pages. Just $16 (but if you read the fine print, you can get a discount.)

This book is not yet available in stores. It's available on Amazon.com and (better for me) by clicking on the cover, you'll be taken straight to my e-store. At $16 bucks, it's a bargain. But you can get an immediate discount by registering, right over here where it says "Writers love readers". Because, we do. >>>

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

Excerpt: October 31—Halloween

The final weekend in October was cold and snowy, although the weather forecast called for it to warm up early in the week. Knowing that our opportunities to fish were waning, Alan, Sarah and I decided to trust the weatherman; we scheduled a day off the following Tuesday, Halloween.

The roads were clear, but there were a couple of inches of fresh snow on the ground, and temperatures were several degrees below freezing when we left. I packed my big rod, a nine-foot, nine-weight Sage blank that I’d built up for steelheading, since I planned to be casting streamers.

On the final approach, up the now-familiar road past the community center and baseball diamond, we passed a black cat, perched atop a fence-post, from which it watched the ditch for signs of rodent activity. In the trees at the diamonds, there is an old white building which I imagine must have been a two-room school, a type common in rural Alberta until the fifties. It would have been wood-heated, and on a cold morning like this, I imagine the teacher would have been glad to have some trouble-making bully she could banish from the class with an order to go out and chop wood for the stove.

We crossed the river at the middle bridge, continuing north and west around the Lazy M, to the upper bridge. With air temperatures so cold, we decided that the water nearer the springs might be marginally warmer. A. and S. both got out ahead of me. I was delayed a few minutes when I realized—trick not treat—that the tip section of my rod had broken just below the top. I tried to reinforce the break with a bit of duct tape, and left the car running so I could tie on my first fly with the heater on.

From the upper bridge, I could cast the big wooly bugger down to one of the overhanging banks I’d discovered on my snorkeling expedition. I hadn’t cast the nine in over a year, and it felt as heavy and stiff as a broom handle. The unaccustomed weight, the cold which had already numbed my fingers, and the broken tip conspired against my being able to form any kind of loop, and the wooly bugger was snagged high in a barren willow bush before it had even gotten wet.

I broke it off, and tied on another big streamer, something that, in the spirit of Halloween, would only appeal to monsters. I was still in sight of the bridge when S. passed me on her way back to the car. “Too cold for me,” she said, “but you fish as long as you want—I brought lots to read.” I gave her the keys and warned her to crack the window if she used the heater. Canadian winters teach you to take carbon monoxide seriously.

I followed A.’s footprints in the snow, up the path along the bank, with the river on my left and a big pasture to my right. Before catching up with him, I turned off the path to the river bank, and began looking for some holes or undercuts past which I could swim my streamer. At a likely spot, I stripped out some line and tried casting, but again found that I couldn’t get anything even remotely resembling a loop. The broken tip was the last straw when it came to casting the heavy line and bulky fly. Again, before the fly had even touched the river, it was hopelessly snagged on the opposite bank.

Stripping the line back through the tip-top, I used a pair of pliers to excise the old tip, clipping it off above the last guide. I tied on a muddler minnow, and decided to add a split shot to the line to overcome the spun-deer-hair head which all store-bought muddlers feature (when I’ve got time, I tie my own, with wool heads that once soaked, sink like rocks). I was struggling to pinch on the shot when I realized, by looking not by feeling, that I was actually squeezing my finger in the pliers. Finally, I got a fly into the water, and instantly felt a little warmer.

The path leading upstream from the upper bridge is tangent to the bank at several points, and while these spots are, no doubt, dredged by spin fishermen, there are few undercut banks which are well suited to a streamer cast down and across, then twitched up in the slow water right against the bank. This strategy did elicit a strike, but it was halfhearted and not the sort of bold attack one expects when fishing the vertebrate hatch.

On every cast, the line would freeze to the guides, and I was tugging it free when I heard A. call out that he was going back to the car too. I reeled in, and trotted down the path to catch up to him. We decided to go into Caroline and have lunch, in the hope that it would warm up enough to give us at least another hour or two in mid-afternoon.

At the bridge, I was surprised to see an angler in neoprene chest waders stringing his rod. He was a stocky, hirsute chap, with a favorable ratio of volume to surface area, the latter well insulated with long hair and full beard. Had he not evidently arrived by car—there was now a second vehicle on the shoulder—I’d have thought it possible he was the troll from under the bridge. I asked him if he fished the Raven often in weather such as this, and he said, “From time to time.” We had a vague conversation about streamers; they’re secretive, those trolls, and I wished him luck.

We drove on west, past the turnoff into Leavitt’s farm and the source springs, then turned south into Caroline. In the Sportsman, we all ordered cheeseburgers and fries on the assumption that we’d eat now and perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation at some later date.

We’d have lingered longer if the coffee had been better, but eventually the thought of freezing on the river was more desirable than another refill. This time, we stopped at the middle bridge, to give the troll some privacy. S. had already fallen asleep in the back seat, after giving us instructions not to wake her at the stream. For his part, A. got out, walked around the car, and got back. He told me that he might fish later, if it warmed up a little more.

It was, at least, above freezing. There was heavy cloud cover; it was nearly dark, even though it was still early in the afternoon. On the western horizon there was a chinook arch, the characteristic gap in the clouds formed by warm winds blowing across the mountains. Chinooks—technically called ‘foehn’ winds—are warm because it’s raining over west of the divide, and wet, west coast air absorbs and releases more heat than dry, prairie air. They are a welcomed phenomenon along the foothills, where they can raise winter temperatures as much as forty degrees in a few hours. This one, however, only warmed me enough to prevent ice forming on my lines.

There was a lot more ice around the middle bridge. In the eddies, ledges of ice were growing out from the banks, and the stagnant, relic channel that joins the Raven about a hundred yards below the bridge was already frozen over. From the parking lot, there are paths leading upstream, and downstream along the pasture, towards the big bend. There is also a path directly through the bushes to the stream, which is visible only a few feet away. These first three or four bends are ones which I had always left for lazier fishermen, but today the snow betrayed no footprints. I decided to begin fishing right at the parking lot.

I tied on a mylar minnow, and picked my way down along the frozen bank. The snow was deep enough to conceal the path surface, and I was concentrating on my footing, and not on scouting the stream. After a few minutes, I looked up and realized I had nearly walked right up to a black eddy, which had been formed where the Raven had eroded a portion of the bank I was walking on. The surface was partially roofed over by twigs and detritus which had gathered in the slack water, and was now frozen to the bank. I pulled up short, and took a few steps back, to a spot where a barren willow would break up my silhouette. It was too dark for polarized glasses, but while I watched the pool, I might have seen a swirl at the surface.

The willow that was providing my camouflage also, of course, blocked a cast directly into the eddy. However, by turning my back on the eddy, I was able to direct a cast above the brush, which on the back-cast drifted out over the main current, where it ran past the eddy. It was not a cast which could have worked with a dry fly, but it allowed the streamer to land in the main current, then ‘swim’ into the eddy in what, I imagined, was a realistic imitation of a minnow entering the eddy for the first time.

The line pulled tight as the fly drifted down and across the current, then slackened slightly as the streamer entered the seam between the current and the pool. Drawn in by the eddy, the fly drifted closer to the bank, and I began to twitch it back towards me.

That eddy is obviously a dangerous place for minnows, as the first cast was greeted by a savage hit. The fish was hooked solidly, and on a 5X tippet, it was capable of putting a good bend into a rod that takes some bending. When it came up to the surface, I saw it was a brown, in the late fall colors which justify the fishes’ name. Measured against the various nicks and scars on my landing net, it was 17 inches long.

As I stepped off the bank into the stream to net the fish, I felt a trickle of water penetrate my waders, so cold it immediately made my foot ache. I released it, and pushed on to the next pool, where, flushed with success, I decided to try for monsters only, and tied on a small mouse.

If anything, the newly shortened rod cast the mouse better than it had before, and the deer-hair rodent looked, I thought, quite lifelike as I twitched it up along banks where long strands of brown, dead grass trailed into the water. As I stood there, the foot I had soaked began to freeze, and I knew I couldn’t last long before retiring to the car.

I heard the hoarse croak of a raven from close by, and looked up to see it flying along the hillside to the north. Off across the pasture to the south, on the other side of the shallow valley, its mate croaked a response. While I don’t speak their language, it sounded as if each was trying to get the other to come to it’s side of the valley, but perhaps their calls were just a way to keep track of each other.

Most English speakers, when they think of ravens, bring to mind Edgar Allen Poe’s famous poem, in which a raven spoke the now-immortal words “never more”. What they generally don’t know is that Poe was inspired to create his talking bird after reading Charles Dickens’ novel ‘Barnaby Rudge’, which also featured a talking raven.

In his introduction to Barnaby Rudge, Dickens wrote a brilliant essay describing his own two pet ravens. These birds were nothing like Poe’s ominous portent; rather, they were curious, entertaining and ingenious creatures. Dickens’ description of the species is entirely consistent with the raven myths of the North American Indians.

To the Indians, Raven was a powerful spirit, also known as the ‘trickster’, no doubt a shaman’s nod to the species’ tendency to mimic the voices of other birds, animals, and even people.

Fly fishers, too, are preoccupied with mimicry. Yet the Raven constantly challenges us to find the thing to mimic, and mimic it exactly enough, without giving the river even glimpse of our fraud. I’ve heard people say, “You can’t fool a fooler” and, likewise, it is inherently more difficult to trick a trickster.

Bernd Heinrich, the ornithologist and animal behaviorist, researched ravens’ social structures in a classic study, Ravens in Winter. In it, he describes the great challenge of trapping the birds for measuring, weighing and banding. Yet, for all their wariness, when they were finally captured, and brought into the confines of his wilderness cabin, Heinrich found that the birds quickly adapted to captivity, and tolerated being handled with aplomb.

After seven months, I certainly still don’t know what it would be like to bring the Raven to hand. Over the season, I’ve heard tell of people who have. They live in Rocky Mountain House, or Red Deer, so the Raven is their local stream. I spoke to one fellow on the phone, who had kept detailed records of twenty years on the Raven, insects seen, temperatures and conditions, successful flies; details that I admit, I’m still remiss in recording. He told me “there are no experts on the Raven”, but mentioned, with pauses while he flipped through his diaries, that he had fished the river on nearly one thousand occasions.

I burned to know, so I asked him, “Do you ever go to the Raven and catch nothing?” Another pause, then “Once, last year.” He volunteered as to how this year had been the toughest year on the river since ‘88, on account of the cold, rain, and high water, and that his biggest fish had run 18 inches. We spoke of getting together to fish the river, sometime in October, so I could check what I had learned, against his more complete knowledge and repertoire.

But few days later, when I called again, and he told me he’d thought the better of it. (He didn’t want his techniques outed to you, dear reader.) I hung up, and thought it better myself: I am certain that my stalking, casting, and ability to read the stream are better now than they were seven months ago. While still an entomological neophyte, my fly selection, and exploratory sequences may be a little more logical, too. I’ve got a long off-season ahead of me, and I’d like to spend the winter thinking I’m on the right track. I can think that, too, since I haven’t seen evidence to the contrary. Better not compare myself to some stranger who claims (and I don’t doubt him) to have caught 25 fish in a single evening, on a stream where I measure success at a single strike per hour.

You can’t trick a trickster, and the Raven is as tricky as they come. It is the biggest small stream I’ve ever fished, and it will never reward a less-than-earnest effort.

Daylight Savings had ended the previous weekend, and darkness was falling by five. The mouse was too crude a trick for the Raven. I reeled it in, and walked back to the car.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)